Open Aquaculture Systems

The aquacultural industry is changing. One of the many reasons is the quickly increasing demand of fish. The per capita consumption has doubled within the last five decades. Traditional aquaculture from over 3000 years ago is not efficient enough anymore for providing the nowadays around 8 billion humans with the needed supply. As a consequence, various systems have been developed or are still being developed to increase the efficiency: pond culture, net cage culture, raceways (or also called flow-through systems) and closed recirculating aquaculture systems (abbr. RAS).

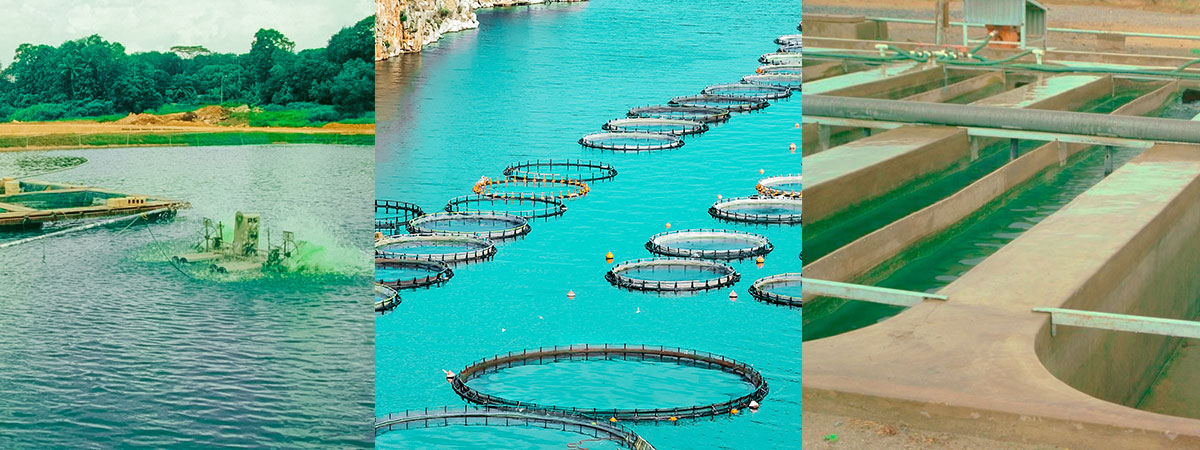

The pond culture is the least technical extensive method; hence it is the worldwide most common system. These pond systems are often family businesses but can also achieve greater commercial sizes. In Europe ponds are usually built artificially and feature a regulated water in- and outlet. The need of freshwater is low compared to other systems, because the stocking density in ponds is lower. Pond cultivation consists of naturally occurring plants and animals, which are not only keeping the water quality up but also providing enough feed among one another. This is called an extensive form of cultivation. Fishes like carp, zander and pike are ideal for pond culture, due to the fact they get along with standing waterbodies. If there is extra feed added, a higher water exchange rate or active ventilation of the water for the required oxygen supply can become necessary.

The net pen or net cage culture is based in natural waters and builds a well-defined habitat within a pond, river or sea, where the fish are being kept. Feeding, controlling and gathering is easier compared to traditional fishing through this defined zone. However, net cages are often operated intensively and thereby a lot of animals with high requirements of feed are kept in a concentrated domain. So net cages can have a grave impact on the ambient ecosystem, because uneaten feed as well as metabolites of the fish end up directly in the surroundings. On one hand, the size of such net pens can vary from small systems from 10 to 150 cubic meters of water, which are representative for Asia. On the other hand, salmon farms in Norway can have a water volume of up to 40,000 cubic meters. Common marine fishes for this kind of aquaculture system are seabream, codfish, salmon, shark catfish, tilapia and seabass.

Raceways are numerous tanks or channels one after another, which water is led through. That is the reason why these systems are also called “flow-through”. The tanks are constructed so that fish species, which are adapted to flowing water, can be held: e. g. trout, seabass or tilapia. Conditioned by the high fresh water inlet, these farms often have relatively high stocking densities and are therefore intensive. From this follows that great loads of metabolites are leaving the system with the water outlet. Before leading this water back into natural waters, it has to be pretreated and therefore makes this aquacultural system compared to these above the most technical expensive.

The closed recirculation system is the most technically demanding aquaculture method of them all. The so-called RAS (recirculating aquaculture system) is reusing the same water by utilizing mechanical and biological filters and treatment processes to obtain a continuously ideal water quality for the kept fish. It is therewith noninteracting with the environment. Such high technical and energetic applications are making RAS quite cost intensive. As a result, this cost pressure often leads to individual large-scale plants. An unmatched advantage of RAS is the complete independence to choose a location for the production, because there are no natural waters needed. Simultaneously they feature high stocking densities, while obtaining a great water quality without losing track of the animal welfare and with a minimal impact on the environment. The SEAWATER Cube itself is a recirculation system with all its advantages. Additionally, this developed system is a standardized small-scale plant for regional production.

The SEAWATER Cube itself is a recirculation system with all its advantages. Additionally, this developed system is a standardized small-scale plant for regional production.

Further informationen about the SEAWATER Cube

Check out more facts about our system and the technology.

References

— FAO (Food And Agriculture Organisation Of The United Nations), 2016. The State Of World Fisheries and Aquaculture. Rome

— Greenpeace: https://www.greenpeace.de/themen/meere/welche-aquakulturmethoden-gibt-es (21.02.2018)

— Timmons, M.B. & Ebeling, J.M., 2010. Recirculating Aquaculture. 2nd ed. New York: Cayagua Aqua Ventures

Image source

Courtesy of FAO Aquaculture Photo Library